May 25th of 2020 started off like any other day for the community of Minneapolis, Minnesota. But at 8:00 PM, the world changed forever. That evening, George Floyd decided to go to his local Cup Foods store to buy cigarettes. Instead, his viral murder at the hands of local law enforcement sparked a national movement that aimed to make community spaces more equitable, safe, and inclusive for minority individuals across the United States.

At the height of the turmoil of 2020, the United States was forced to confront the inherent injustices that many of its citizens faced daily. However, on January 20 of this year, the Trump Administration issued a series of executive orders targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in the private and public sectors. Designed to prohibit lawful efforts to advance equal opportunity, the administration declared that diversity, equity, and inclusion offices, positions, grants, and programs must end in both the federal and public sectors.

If they fail to do so, the Trump Administration claims that they could be subject to lawsuits or may lose government funding. These edicts are not only based on misinformation and illegal, but they could also potentially endanger the American economy as a whole if wage gaps cannot be closed.

Equity and inclusion efforts have been attacked since before Trump stepped into office for his second term. In Texas and Florida, education has been targeted, with threats to remove pivotal historical literature regarding race and sexuality from school curricula.

However, with this new series of orders, the country is now even further plagued by an impending fear that any progress made in the past half-decade could be completely eradicated, once again sending Americans decades backward.

Lori Patton-Davis, a member of the National DEI Defense Coalition and Heyman Endowed Chair in the School of Education at UCLA, explained that “[DEI Programming is] about tapping populations or groups who have not been treated equitably and providing the space for them to have a full life. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. But there are lots of different barriers in the way that prevent those things. And so there are policies and processes that make it possible to remedy issues of exclusion.”

However, while many higher education experts believe in the program’s initial intended purpose of diversified recruitment practices, at some point, some Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion(DEI)-branded organizations made the mistake of emphasizing essential differences between people of different racial groups instead of their commonalities.

Robert Maranto, a political scientist and professor at the University of Arkansas who supports the removal of DEI initiatives, notes that while they could work in the future, they certainly do not work now.

“Having a special unit, a chief diversity officer for a corporation, doesn’t make corporate leadership more diverse. Having a chair of equity for a school district doesn’t seem to lower achievement gaps; if anything, it might be associated with larger achievement gaps,” he said.

For Maranto, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility (DEIA) programs in their current state have been used to censor free speech on both sides of the political spectrum while requiring representation in areas that didn’t really need them, like DEI components in research grants. However, he disagrees with the Trump administration’s dismantling of equity initiatives, which he sees as an extreme overcorrection to DEI requirements mandated during the Biden administration without proper dissection of the program’s potential benefits.

Local Protests and Platforms

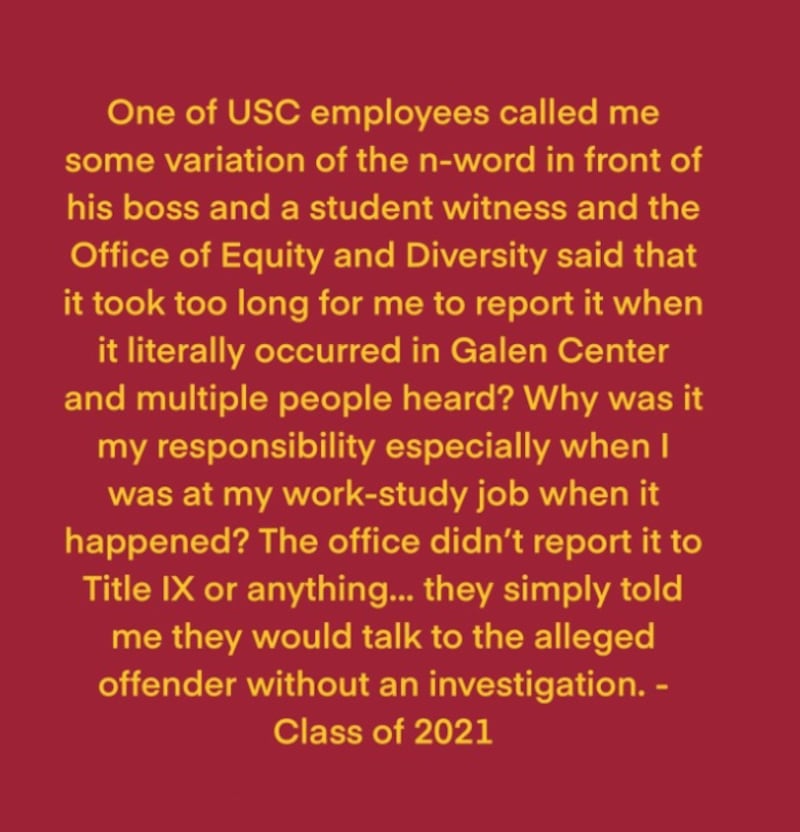

After the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, many students in both high school and college grew tired of the growing racial injustice they saw while trapped in their homes and decided to take action. While protests and petitions were a popular form of advocacy that summer, another method of racial equality advocacy was through social media. One of the most prominent of these online platforms was the nationwide “Black @” movement, where students, alumni, and faculty at some of the country’s most elite schools around the US submitted anonymous accounts of their encounters with racism, microaggressions, and more at their majority-white institutions.

The “Black @” social media movement spread through Instagram stories and hashtags, showing that racism and discrimination in education spanned across multiple states and generations.

At USC, one student chose to create the @black_at_usc Instagram account to hold the school accountable for the ways that students of color and LGBTQ+ students were being mistreated by classmates, professors, and staff around campus. They have requested to remain anonymous due to fear of repercussions from USC and to maintain the intention behind the anonymous Instagram account.

With a following of 10.2k, @black_at_usc became extremely influential in advocating for equity on campus. It, paired with protests already happening on and around campus, inspired the implementation of new Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion efforts on campus.

But half a decade since the account’s creation and the establishment of DEI policies throughout the university, the world seems almost completely different.

When the @black_at_usc account launched, the university went wild. Within hours, posts started flooding in, detailing the discrimination they had faced in the USC community. Posts were shared across multiple platforms and quickly gained the attention of the University. However, while students appreciated the outlet to express their grievances with USC, school administrators were not as supportive.

The @black_at_usc’s creator voiced their concerns with the feedback from USC during an interview with Annenberg Media. “[The administration] didn’t seem too pleased with the way that I chose to run the page. It took countless people tagging the @uscedu Instagram page to finally hear from the administration, and, even then, the solutions they came up with were DEI committees and similar bodies,” said the creator.

Professor Miki Turner, a University of Southern California Annenberg professor and faculty member, was inspired by student movements across campus to encourage change in Annenberg. Turner created the Annenberg Cross-Cultural Student Association (ACCSA), which produces multimedia content that amplifies underrepresented voices on campus and sheds light on issues that might not otherwise be addressed.

Turner created the ACCSA in response to the university’s inherent biases against minority groups in the USC community to enable professors, faculty, and students to advocate for diversity and equal representation in Annenberg. She galvanized the Annenberg faculty to give students a forum to express how they’re feeling and to know that they have support from the Annenberg faculty.

“You can’t turn a blind eye to what’s going on. You have to try and create some plan of action so that this systematic type of racism and discrimination doesn’t continue in its present form,” Turner said.

However, with the reluctance of the administration to confront issues regarding accusations of racial discrimination on campus head-on, many have begun to lose hope that drastic change could ever be made. Professor Turner and many faculty members like her connected the university’s inaction to the problematic systemic nature of the university system in general.

“The issue that you have is a lot of these professors who have been either mentioned at @black_at_usc or there have been hints that so and so teaches this class, they are tenured – you can’t get rid of them,” Turner explained. “And again, you can’t change people. You could have all the workshops, and all the seminars, and all the mandatory seminars and whatnot, and it’s not going to really have the effect, I think, that the administration would hope it would.”

Providing further insight into how university faculty operations worked, Turner recounted how sometimes it seemed like the university would simply wait for each complainant to graduate while acting as if to be deliberating for a few years so that they would never have to address the issue.

“Typically, what happens at SC is that the administration tries to solve a lot of these issues with research, by looking at a textbook and saying, ‘What should we do?’ Or they ask all the professors of color and staffers of color, ‘Oh, what do you think we should do?’ when all it is is a common-sense solution,” Turner said. “Solving these issues is difficult because everyone has a different idea of how to do it, and even with the creation of all of these diversity and inclusion offices and departments, no one has gotten it right.”

Similarly, the @black_at_usc creator went on to voice that more could be done to inspire change in the community.

“Don’t get me wrong, there is nothing inherently wrong with such committees. The problem is that, too often, the initiative stops there — not much more effort is put into actually affecting tangible change.”

Equity or Erasure

At USC, the effects of revoking DEI policies have been profound. Its Office of Inclusion and Diversity was dismantled and merged into a new organization that promotes community and cultural advancement. Several department-level DEI statements were erased from university platforms, and in one case, online references to a Black and Indigenous scholarship opportunity were removed.

At first, students held out hope that USC would not succumb to pressure from the administration. But as prominent universities began to give in one by one, USC attempted to covertly alter its equity policies to protect itself from any federal retaliation.

What this meant was disbanding USC’s Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion while simply giving administrators of DEI a new title. Additionally, USC has begun to replace any reference to DEI with terms like “community” and “culture”.

Lori Patton-Davis noted that this may just be the next in a long line of language changes used in cultural organizations to allow them to move forward. “If you look at the history of culture centers, particularly the black culture centers, a lot of those were called minority affairs,” she explained. “By the time you get to the ‘70s and ‘80s, the language is shifting to multiculturalism. And by the time you get to the ‘90s, it’s pluralism. And by the time you get to the early 2000s, it’s social justice. So the language around DEI has always been there. Issues around access and equity have always been a part of what people have been fighting for in this country.” For her, she hopes that renaming DEI in place of language like “offices of advancement” is just the newest in a long line of efforts to remedy barriers put up due to racism, sexism, and homophobia.

However, for researchers like Patton-Davis, simply changing a title could still leave universities under scrutiny. In thinking about how DEI programs are under scrutiny in Texas, Patton explained that “You have state legislators coming in saying to change [DEI titles]. They’re not just going to look at how you change your name or change the title of your course. They want to read the syllabus, the programs, and all of that. And so at this point, it may not be enough to just change the name and continue to do exactly what you are doing. You might also have to shift your curriculum or shift your programming so that it is clear that your office or your unit is there to support all students.”

With the 2023 Supreme Court decision that outlawed the consideration of race in admissions, many students across the United States are wary of how policies like this could appear in student life.

Nationwide, educational institutions have taken different stances on whether or not to succumb to the Trump administration’s ruling. However, while universities remind students that they will continue their efforts to promote “community” on campus, many students worry that even slightly giving in to Trump’s new policies shows that the school will not stand by its students when the time comes.

Reflecting on past DEI services, recently graduated USC student Feben Worku doesn’t think the faculty had taken it upon themselves enough to create change.

“It feels as if most people of color, when they do speak out about this, it’s twisted in a way that it makes it seem as if they’re not the victims,” said Worku. “I think that’s a big reason why a lot of people don’t speak out – just because, when they do speak out, their voices are often overlooked or just put down in a way that their issues are not being fully addressed. Students often have to list the problems and find the solution for faculty when it should be the other way around.”

At UCLA, Patton-Davis said that the loss of DEI initiatives felt like a punch to the gut for faculty trained to support their students.

“It’s hard to be doing the work that matters and the work that you’re being trained to do,” she said. “And to also be gaslit and told that you’re doing it wrong, or you’re doing it in a way that is no longer in alignment with federal or state policy – depending on what state you’re in – I think it makes people question whether or not this work ever mattered.”

For Patton-Davis and many other supporters of the initial intent of DEI, the eradication of equity programs highlighted how many promises made to minority students since George Floyd’s death seemed to disappear.

“Right now, we get to see that a lot of corporations were really more performative in nature, not really committed to this work or some of our institutions,” she said. “ It’s more of a window dressing, but that wasn’t really a commitment. So that is very disheartening for many folks who are working in offices that might have typically fallen under a DEI. umbrella.”

What’s more, Patton-Davis pointed out how the removal of DEI positions has led to a rising number of unemployed women of color around the country who tended to rely on and even lead in these types of positions.

Having lived through the civil rights movements of the ‘60s and ‘70s, Professor Turner felt she was experiencing a repeat of what had happened in her youth, only in a different form. To her, she doesn’t think the events of 2020 have had any real impact on what is happening today.

“This feels even more toxic and dangerous than it did when I was a kid in the ‘60s, because at least we had movements in the ‘60s,” Turner said. “There’s no real movement now to stop this madness. And I think it’s because it just caught a lot of people off guard. All you had to do was open your eyes to see what was right. But with [Trump], people just thought, oh, it’s gonna be okay. He’s gonna do this and do that, it won’t affect me. But like I said before, it’s affecting everybody. And once it starts to affect the people who have, for the most part, been privileged and entitled most of their lives, they’re not equipped to know how to deal with it. People of color are. We have been through this before”.

Richard Kahlenberg, director of the American Identity Project at the Progressive Policy Institute, has studied racial and economic diversity in higher education for about 30 years. While he notes some of DEI’s pitfalls, he states that “I do worry that the Trump administration is going way too far in telling universities that they can’t consider economic disadvantage as a way to create racial diversity. That’s not what the Supreme Court said, and I think it’s a misreading of the Students for Fair Admissions versus Harvard decision.”

This decision, while largely considered on a racial basis, in many ways revealed how sometimes economic disparities are tied to race and environment.

Finding Community in Chaos

While the Trump Administration continues its agenda to eradicate spaces for minority voices, USC still has spaces like the Center for Black Cultural and Student Affairs (CBCSA), which aims to provide educational programming meant to strengthen youth leadership and awareness, an understanding of Black culture and heritage and a space for Black students to connect. Turner believes that organizations like that are key to creating community.

“We have so many different types of Black students who are at SC – I mean, you have celebrities’ kids, we’ve got a former president’s kid here, we’ve got first gens, people who are upper middle class, lower middle class, etc. – we’ve got this whole melting pot of Black life at SC and I think there has to be some way for all these groups to come together and decide on a course of action to determine what it is that would make that experience better for them,” said Turner.

While the country’s current situation looks dire, many still have hope that things could improve if people finally get together to discuss what is going on around them again in an open and honest setting.

“I think that [universities] just really need to listen to their students,” said Worku. “Not in terms of passive listening, where you’re asking for people to show their opinions, but I think that proactive change needs to be made.”

In place of DEI, Richard Kahlenberg suggests a program that emphasizes integration, equal opportunity, and belonging for all communities regardless of race, gender, or political affiliation. “The difference between integration and diversity is that diversity emphasizes difference,” he says. “Integration emphasizes what we share in common: humanity.”