What started as a police ride-along in Watts turned into a groundbreaking community film — one that captures the city’s resilience, unity, and hope through the eyes of its own residents.

A powerful new documentary made entirely by residents of Watts captures the city’s resilience, unity and hope — proving that storytelling can spark real change.

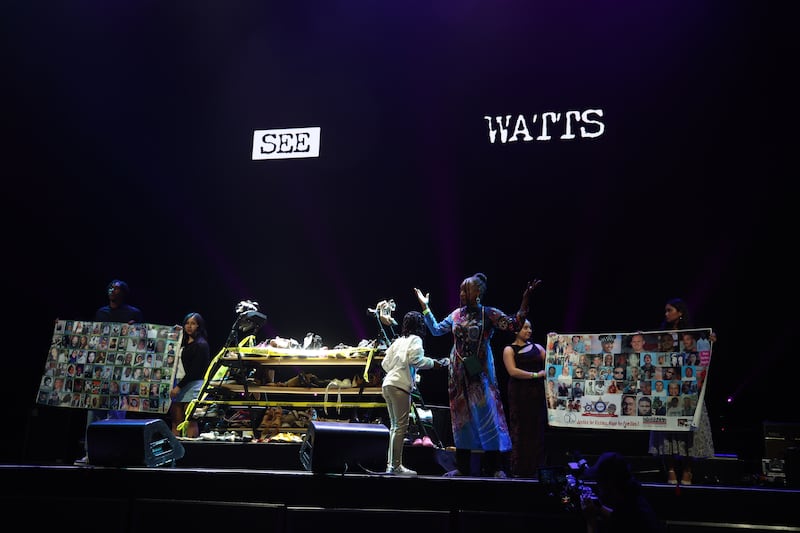

The energy inside the Peacock Theatre on the evening of October 10 was electric — a celebration not just of film, but of community. As an orchestra played and the smell of popcorn filled the air, the words “See Watts” glowed across the middle screen while trumpet notes danced through the space. For one night, 5,000 people came together to honor a city too often misunderstood — and to witness what happens when a community takes control of its own story.

The evening began with a live performance by filmmaker and activist LaWanda Hawkins, whose “Silent March” — featuring more than 200 pairs of shoes representing children lost to violence — stood as a solemn tribute to the innocent lives taken too soon.

Hawkins isn’t a Watts native, but she has long been part of its fabric. In 1996, she founded Justice for Murdered Children (JFMC) in Watts after the tragic loss of her son Reginald, who was murdered the year before. Her organization advocates for families seeking justice and healing in the wake of violent loss.

“Not only Watts, but all communities in Southern California — maybe even beyond — can learn from this,” Hawkins said. “It sets a blueprint. It shows that communities can come together, even during difficult times. We may not agree, but we can still come together and have those hard conversations people are sometimes scared to have.”

Her message of unity through art mirrored the spirit of the night’s screening. As the final notes of “Silent March” faded, the lights dimmed for the premiere of the 90-minute documentary “Nothing to See Here: Watts.”

There was no director. The film was shot with only phones in the hands of those who live in Watts every day. Over three years, residents from rival neighborhoods — including members of the Bounty Hunter Bloods and PJ Crips — pastors, police officers and students filmed their lives, their losses and their hopes. The result is a raw, self-made portrait of resilience.

The idea began with Michael Soenen, a volunteer with a local organization called the Healthy Room Project, which helped refurbish bedrooms for children in Watts. During a police ride-along, Soenen witnessed a shooting that claimed a man’s life — an event that never made the news. The experience left him questioning how little the outside world really understood about Watts.

He decided to do something about it. Soenen bought 20 iPhones and began handing them out to residents, asking them to document their daily lives. Out of 200 people he approached, only 20 agreed. “I’d never made a film before — not even wanted to,” he said. “It wasn’t supposed to be a movie; it was just meant for me to learn.”

As footage started coming in, Soenen realized the power of what they had captured. Instead of deciding the story himself, he gathered the participants and offered to provide editors, technology and resources — but only if they became the filmmakers. “The only way we would turn this into anything was if all of them became the filmmakers,” Soenen said. “And they did. It took about a year, but they made the film.”

At first, he said, many were hesitant to record their stories. “Every one of them said either no one’s ever asked me to, or they didn’t think their story was special,” he said. “But as they started to see each other’s footage, that’s what built momentum.”

Soenen said trust was the foundation of the project, especially with participants from rival gangs. “They owned all their content,” he said. “If they didn’t like how it was edited or portrayed, they could always leave. That’s how the trust started.”

Despite challenges from local institutions and skepticism rooted in past documentaries about Watts, the team persisted. “We had nothing but challenges,” Soenen said. “You’ve got somebody who doesn’t know how to make a film, 20 people who don’t know anything about making a film, and everyone against it because of bad prior experience — but we made it happen.”

Executive producer Suzanne Malveaux described the project as a living example of transformation.

Malveaux said the project began with a simple idea: give people the tools to tell their own stories and see what happens when a community documents itself.

“Just through the exercise of making a film together, the community revealed their innermost selves,” she said. “It’s been a catalyst for change. Rival gang members, police, community members — they’ve developed friendships and empathy that didn’t exist before.”

The film’s heartbeat comes through its soundtrack — featuring Chris Brown, Jhene Aiko, Victoria Monét, SiR, Leon Thomas, Kehlani and Lalah Hathaway, who felt deeply connected to the project.

“It was a beautiful thing,” Hathaway said. “I’ve been here about 35 years, and I feel like a native. To be able to contribute to something for the city, for Watts — it’s really special. I hope it makes people want to understand who the artists are, where they come from, what the legacy of that space is.”

The film opens with a striking image — shoes hanging from power lines — before unfolding into personal stories of faith, family and perseverance. One of the most powerful stories comes from Tyrone Riley Sr., a high school basketball coach whose mother was murdered in front of him when he was a child.

“We crammed three months of work to get in this film,” Riley said. “I just want to show the community that we came together. Hope — because it gives the community a chance to dream about something else.”

His son, Tyrone Riley IV, a student and aspiring athlete, echoed his father’s optimism. For both father and son, the project became a shared mission — to replace fear with hope and show that change in Watts begins with those willing to tell their truth.

“Most people think of Watts and they think of violence,” he said. “That’s not the persona we have. We’re trying to change that.”

Former gang member turned pastor Jose Hernandez said the project’s greatest power lies in ownership.

Hernandez, who now mentors at-risk youth and leads outreach programs across South Los Angeles, said he was drawn to the project because it allowed residents to reclaim their own narrative — not through statistics or headlines, but through lived experience.

“This movie doesn’t have the solution, but it can be a catalyst,” Hernandez said. “Usually an outside source prescribes how the story’s told. This one’s self-made because we’re telling it — we live here, we serve here, we raise kids here.”

Nearly half of Watts’ residents are under 24, and the neighborhood has one of Los Angeles’s lowest life expectancies.

He explained that the film highlights more than statistics — it puts faces to the numbers. By centering young people’s stories, it challenges the stereotypes often associated with Watts and shows the potential that exists when the community invests in its youth.

Yet Hernandez’s message was rooted in hope.

“You expose young people to hope,” he said. “When they have hope, they’re not going to pull the trigger — because they have something to lose.”

Moments from the film captured that hope vividly, including a scene where rival gang members Cornelius Wills and Riley Sr. sit at the same table — a quiet symbol of reconciliation.

The moment drew a hush from the audience — a reminder that healing often begins in small, unseen ways. What once seemed impossible in Watts was unfolding on screen: two men from opposing sides, sharing space and understanding instead of conflict.

“This film will hopefully bring hope for the city,” Wills said. “I want people to feel like we can get ours together and be safe like any other city.”

The evening ended on a powerful note as Grammy Award–winning artist Kim Burrell, Grammy-nominated singer Kenyon Dixon and Salaam-Bailey, the film’s composer, joined the Roc Kids Choir to perform “Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” an original song from the film’s forthcoming soundtrack.

Among those in attendance was music legend Stevie Wonder, as the theatre filled with harmonies blending gospel, R&B and soul — a fitting finale for a film that transforms pain into purpose.

Attendee Latonya Jackson left inspired. “It helped bring more unity together,” she said. “It made me want to go out in the community and do something — no matter what it is — so people know there’s always someone willing to help. It was motivating to see everyone come together like that. We need more moments like this in our city.”

As the crowd filtered into the night, one truth felt clear: Watts isn’t just being seen — it’s finally being understood.

“I’m hoping people walk away knowing they have the power to change their communities — just by listening to each other,” Malveaux said. “What’s possible in Watts is possible anywhere.”