Courtney Brink, a 23-year-old American in Hamburg, Germany, stayed home from work to watch election returns last November. Spirits ran low among her circle of American friends. When Donald Trump’s victory was confirmed, she felt a deep sense of uncertainty about her future and whether she could return to the country she had left behind as long as he remained president.

“I don’t want to live in America for the next four years because I find Trump unpredictable,” Brink said. “Trump is a poor representative of our country. His immaturity is pretty embarrassing.”

She plans to extend her Fulbright grant, which offers U.S. funding for teaching or research abroad to foster cultural exchange, for another year and apply for jobs to remain abroad throughout Trump’s presidency rather than return to her home in Omaha, Nebraska.

A growing number of young Americans are contemplating life outside the U.S., citing concerns over political instability, right-wing rhetoric and their safety.

A survey by Immigration Advice Services, a UK-based private firm offering immigration legal assistance, found that 40% of Americans aged 16-24 are considering leaving the U.S. in response to the country’s political climate. While Canada and the U.K. are the most popular destinations, some are setting their sights on Germany — even with the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) becoming the second-largest political party in the German parliament after the February 24 election.

Officials are noticing the trend.

Danijel Skrelja, deputy consul general of Germany in Los Angeles, said his office has seen an “uptick” in queries about German citizenship and residency.

Although he declined to disclose specific figures on applications or residency permits because of strict privacy policies, Skrelja noticed a shift after November.

“This increase for requests or just for general information is especially visible ever since the U.S. election,” he said.

A wave of executive orders

Brink, who is currently a Fulbright teaching assistant, says her decision is driven by more than political disagreements — it’s about her future aspirations.

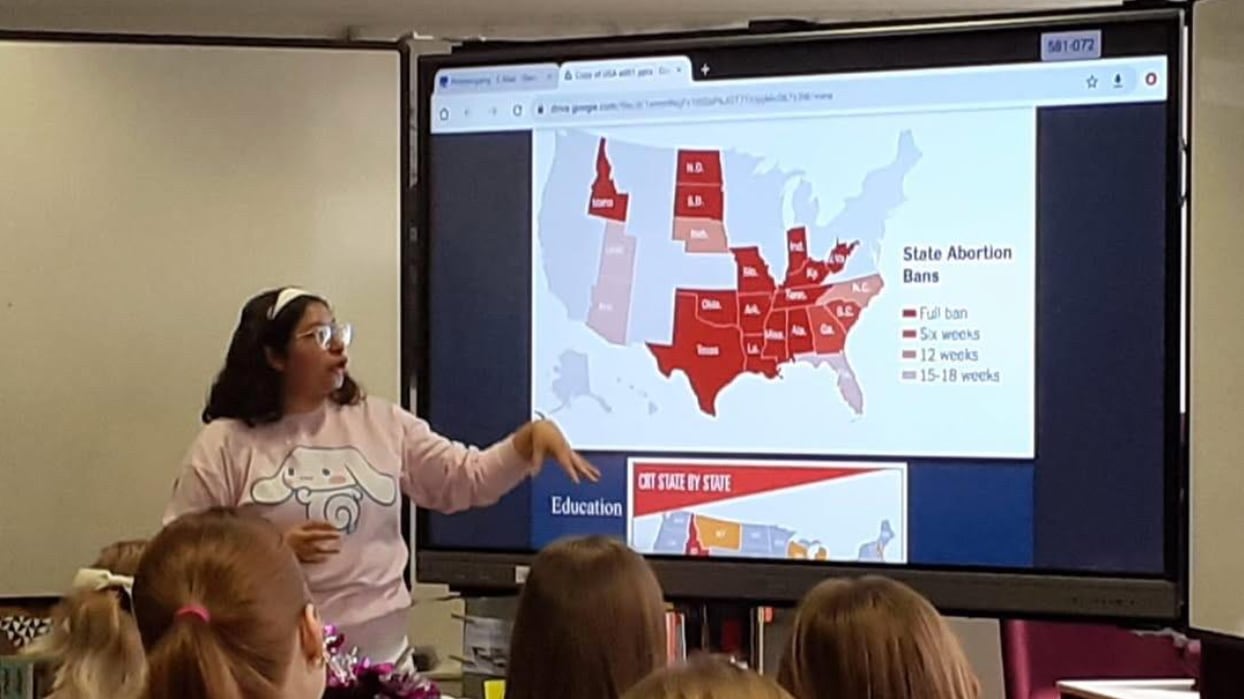

As an aspiring teacher, she worries about the state of American schools, especially amid reports that the Trump administration is considering executive orders to dismantle the Department of Education, ending programs supporting diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), which she says would harm queer individuals like herself.

“I have a lot of queer and trans friends,” she said. “I think that can get really isolating when you have people at the top level pushing traditional family structure.”

Beyond the rollback of DEI programs within the Department of Education, Trump also signed executive orders targeting the transgender community. These orders restrict federal gender markers to sex assigned at birth, expand the transgender military ban, and curb gender-affirming care for Americans under 19.

Norma Martinez, who is currently living in Cologne, Germany, fears what the future in America holds and how it could impact her.

“I want to pursue an education, but how do I do that if I don’t have any kind of support?” she said.

Martinez grew up in a low-income household in Southern Georgia and financed her college education through government funding sources, including the Pell and HOPE Grants. The Pell Grant provided financial assistance to low-income students, and Georgia’s HOPE Grant helped cover tuition for residents pursuing higher education within the state.

The administration of federal loans, like Pell Grants, would change if the Trump administration follows through on its plan to abolish the Department of Education. Martinez’s concern was amplified when the White House temporarily froze federal grants, only to reverse the decision two days later.

Martinez is not concerned about financial barriers in Germany, though, where she notes that education is more accessible.

“I can pay about maybe 200 euro[s] and I can get a scholarship. So there’s more affordability,” she said.

Martinez’s decision to stay abroad is also one that is deeply personal.

Her father worked in a chicken factory and lived in poverty throughout his life. In the 1970s, he immigrated to the U.S. illegally from Mexico in search of better opportunities to provide for his family. During this process, Martinez’s parents were separated from two of their daughters, who still live across the border in Mexico.

“My parents were in child labor for most of their life. They were in poverty in Mexico,” she said, showing postcards she sends her family. “My parents didn’t want their children to have that. So they came to the U.S.”

Martinez now sees the anti-immigrant backlash that shaped her childhood intensifying under the new administration. Her friends have already reached out to her, telling her that Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has shown up at their doors in Georgia, searching for undocumented immigrants.

Just hours into his second term, Trump signed a series of executive orders with significant consequences for individuals like Martinez’s father. Some of these included declaring a national emergency at the U.S.-Mexico border, seeking to end birthright citizenship, and enforcing stricter immigration policies through the Department of Homeland Security.

Since Trump took office, his Border Czar, Tom Homan, claims that ICE has arrested around 14,000 undocumented people.

“This is hitting something very close to home and to my heart because that’s even why I chose to pursue my education in university,” Martinez said. “It was to help mainly immigrant and migrant communities because I know what the government can do.”

Weighing the risks in Germany

While factors like personal safety and education make returning home less appealing, and Germany emerges as a more promising option, the country is not without its political challenges. The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has gained traction, raising concerns among immigrants and minorities.

The AfD, or Alternative for Germany, is a far-right political party known for its stringent stance on immigration. The party has been vocal in advocating for limiting immigration, particularly from Muslim-majority countries, and opposes policies that promote multiculturalism.

Martinez, who spent time in Germany, recalled her experience in Görlitz, a town in the eastern part of the country, where many of her students’ parents supported the AfD.

“I got a warning from one of the teachers,” Martinez said. “Many of their parents are part of the AfD, and they probably haven’t interacted with someone that looks like you.”

As Martinez spoke with the students — nearly 100 packed into a cramped classroom with chairs shoved together — she answered their questions about immigration and identity. The group, made up of 12th and 13th graders, included a mix of backgrounds: three students of color, a dozen students from Poland, and others who had lived in Germany their entire lives. Yet, as Martinez shared, many locals still saw immigrants as outsiders, regardless of how long they had lived in Germany.

“No matter what you do or how long you’re there, you’re never going to be seen as German,” Martinez said. “You could be there for five generations, but if you’re not white and don’t have German ancestry, you’re never going to be seen as German.”

Brink, who has now spent almost a year in Germany, agrees with this sentiment. She learned much about the AfD from her roommate, who participated in protests against the party.

Brink’s decision to stay in Germany was largely influenced by concerns over gun safety and the political climate in the U.S., which she feels makes the situation in Germany seem better in comparison.

“I graduated from Millard’s Health High School, where there was a shooting when I was in elementary school,” she said. “Attending that district and potentially working there makes me nervous — coming to school knowing that anyone could have a weapon or enter the school.”

While the rise of the AfD is a concern for some Americans, Germany’s “special partnership” with the U.S., means that many Americans interested in relocating face fewer barriers.

The U.S. is among the countries that can enter Germany without a visa for employment or vocational training. However, a residence permit must be obtained in Germany. For anyone planning to start work soon after arrival, it’s recommended to apply for the visa before entering the country, according to the German Federal Government’s website.

Despite the anti-immigrant and right-wing rhetoric of the AfD, both Brink and Martinez see Germany as offering more stability than the U.S. Brink highlighted the country’s healthcare system, gun laws, and overall sense of public safety, which she sees as making it a safer alternative. Martinez, while acknowledging Germany’s challenges, feels that leaving the U.S. was the right decision for her future.

Skreja, a German foreign officer in the U.S., said people looking to move to Germany often overlook the country’s current political issues.

“People want to move to Germany because they are not happy about the political climate here in the United States,” he said. “The political climate in Germany often is of no concern to them, we find.”