The University of California could have prevented its largest labor crisis at the bargaining table.

Instead, as professors cancel lectures due to teaching assistant shortages, lab sections pause crucial lessons and undergraduate assignments go ungraded, the university’s pattern of intimidation and foot-dragging becomes less a tactic and more a liability in negotiating against 48,000 striking graduate workers — the university’s backbone for all day-to-day curricular activities.

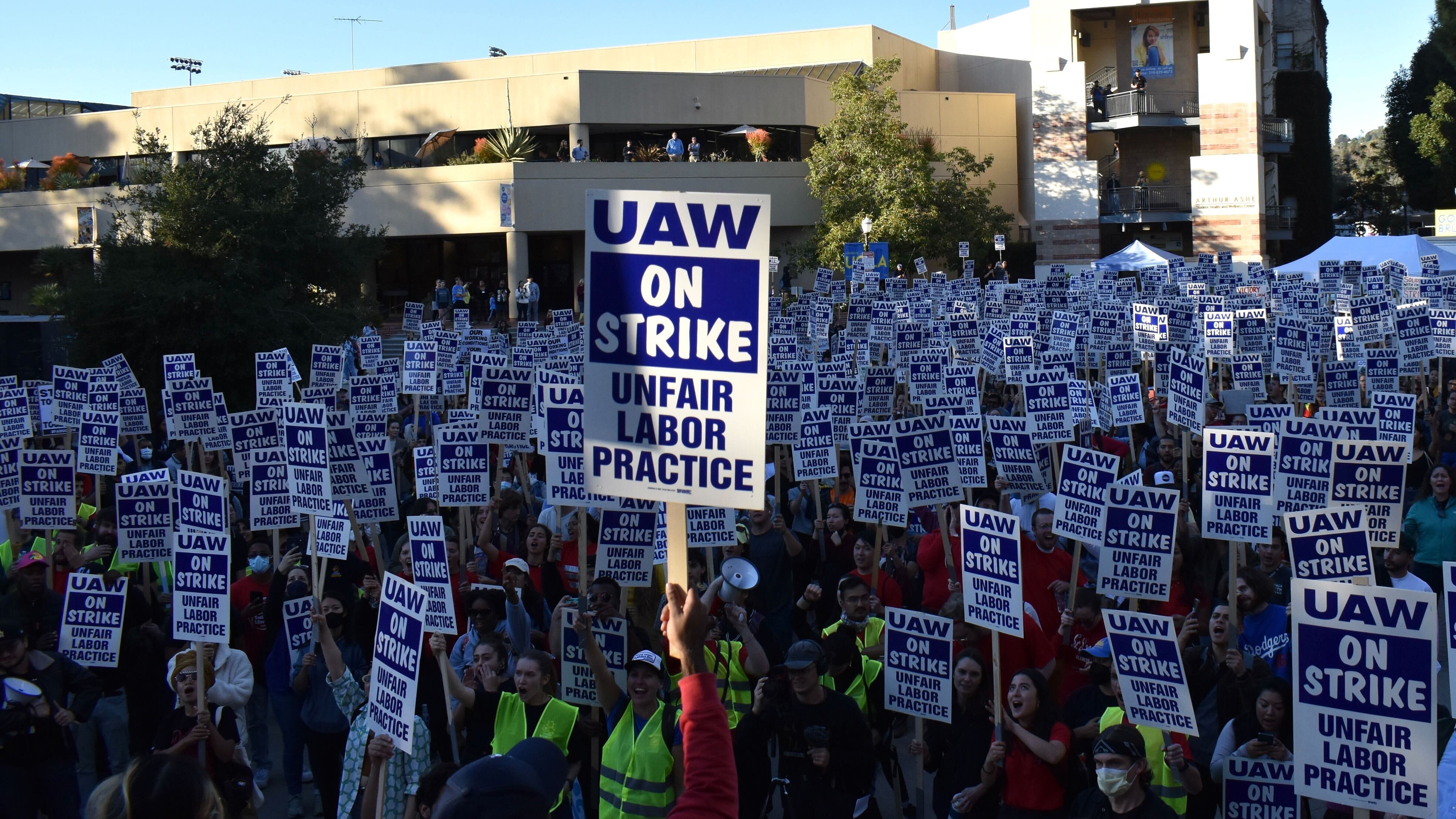

The nation’s largest ever strike of academic workers has been a long time coming, according to Michael Dean, a seventh-year doctoral candidate in history at University of California Los Angeles — not only because the university has stalled open negotiations since March 2021, but also because it has engaged in numerous illegal negotiation tactics with the four union bargaining units.

“Rather than come to the bargaining table and negotiate with us, the university has decided to engage in a variety of unlawful tactics at the bargaining table, ‘’ said Dean, a lead member of the United Auto Workers unit 2865 bargaining committee. “Refusing to negotiate in good faith, refusing to provide us with the information that we need in order to bargain — that we have the right to ask for — in order to bargain unilaterally.”

When Dean first moved to Westwood in 2016 to attend UCLA, he paid 69% of his paycheck back to the university in the form of rent. The average UC graduate worker earns $24,000 a year, according to the UAW.

“Currently, many of us pay 50, 60, 70, even higher than 75 to 80% of our income [in rent],” Dean said.

Under the Higher Education Employer-Employee Relations Act, employers must meet various legal obligations when bargaining with unions. The Student Researchers UAW Union has filed 37 charges through the Public Employment Relations Board, alleging labor violations such as abrupt policy changes outside of bargaining, refusal to share necessary information and direct survey of unit members about policies under negotiation.

As of Dec. 6, PERB has officially recognized 15 of these charges against the UC as unlawful labor practices.

Dean said the UAW submitted nearly 150 information requests from the UC to create reasonable proposals about nonresident tuition, housing subsidies, transit costs, dependent healthcare and childcare programs.

“We’re trying to figure out, what impact is this [policy] going to have on the university if we were to waive this? What do they cost? How are those costs decided? How many people are taking advantage of them?” Dean said. “And the university just refused to provide information on most of them.”

Ahmed Akhtar, a sixth year doctoral candidate and student worker in the physics department at UC San Diego, has been organizing with the Student Researchers United UAW union since 2017. As elected bargaining team representative for SRU-UAW, Akhtar represents 17,000 researchers that perform experiments, collect data and do the work that makes the UC a prestigious research institution.

“It doesn’t seem like [the university] respects our time,” Akhtar said, adding that negotiation representatives from UC Labor Relations have frequently been late to bargaining sessions and spoken condescendingly to unit members.

Protective measures against racial discrimination, sexual harassment and faculty bullying in the workplace, proposed by Akhtar and his colleagues at SRU-UAW, had all been halted in negotiation due to the university’s abstentions, said Akhtar. That’s part of the reason 96% of union members voted in favor of a strike.

“It really is in contrast to the university’s stated position of caring about equity and diversity, being a progressive force for social change,” Akhtar said. “If the UC wants to be seen as a truly public institution, it has to make itself accessible to people from middle class backgrounds.”

According to the SRU-UAW, the UC has tried to intimidate union workers at least eight separate times.

On Nov. 23, the union reported that after a UC San Diego student emailed other graduate students to rally support for a letter to the chemistry department leadership, one professor called for the student’s firing and another personally emailed him, saying “it’s important that you…not engage any further in any form or shape on the issues surrounding your letter.”

In October, union members at UCSF “witnessed…a recently-tenured UCSF faculty

member angrily ripping down all the UAW posters,” which was repeated at least four times thereafter.

The UC repeatedly weaponizes graduate workers’ dual status as degree-earning students. Over the past several months, it has threatened to fail, penalize and dismiss grades or course credits if workers participate in union activity.

On the first day of the strike, the UCSD chemistry department’s vice chair threatened that student-employees who stop work “because of the strike” may receive an unsatisfactory grade in two required courses, reported the union. At UCLA, the School of Music Dean Eileen. L Strempel emailed graduate students saying “there is no protection” for students who choose to strike, and that “[a]ll students” should attend class or else “the professor should penalize them.”

In response to the UAW’s Nov. 14 notice to strike, leadership at the UC Santa Cruz engineering department emailed workers stating that “the right to withhold labor does not apply to academic work” if courses are involved. But, the only reason for workers to enroll in these courses is to perform work as researchers and teaching assistants.

At UC Davis, UC Graduate Program Coordinator Amanda Turner threatened to revoke workers’ financial aid if they continued to strike.

The HEERA clearly establishes that universities cannot threaten the right to unionize or withhold labor by interfering with the student portion of their dual status. Their work, roles and achievements as students and employees are one and the same.

As the strike continues into its fourth week, Dean said the UC still refuses a 14% salary increase that would account for basic inflation rates and rising rent in California.

“They’ve offered us a 7% [increase] in the first year, followed by 3% every year after,” Dean said. “And that’s not even close to [the cost of living]” increase and inflation rate this year.

The UAW’s proposal, Dean emphasized, asks for only 3% of the university’s total budget to compensate the entire graduate workforce.

“Undergraduate tuition is one of the largest portions of the overall budget,” said Tobias Higbie, a professor of labor studies and history at UCLA. “It’s circulating around the university to pay for education, but also to pay for beautiful gymnasiums and dormitories and other things like that.”

“Just like a private school, [UC] has to appeal to those tuition-paying families so that they feel like they’re getting their value in coming to UCLA,” Higbie added.

That’s likely why the university dismissed and delayed negotiations until three weeks ago, when the UAW strike infiltrated its front-facing operation across media coverage of all 10 campuses.

“The UC recognizes that an academic worker strike would hurt their branding and messaging as a socially progressive force in California,” Akhtar said. “If its core mission is doing the cutting edge research of an elite educational institution, you can’t do that without teaching assistants, student workers and staff.”

Last Tuesday, postdoctoral workers and researchers reached a tentative agreement with the university, raising the minimum annual pay for full-time positions from about $55,000 to $70,000 or higher, including a $12,000 raise by next October. The agreement, which applies to roughly 12,000 of the total 48,000 UC graduate workers in the union, represents the first major step forward in a nearly 20-month stalemate at the bargaining table.

“We are proud to have reached agreements that address the soaring cost of living, and reflect the value of our contributions at UC,” said Neal Sweeney, president of UAW unit 5810, in a statement. “These agreements represent a new, best-in-class model that will improve quality of life — and the quality of research — for scientists across the U.S.”

Dean said the bargaining units have also made historical agreements about bullying and harassment in the workplace. But, the UC and UAW remain far apart on major policy proposals, including compensation, that could signal an end to the strike.

“We continue to be ready and willing to consider fair proposals, whenever the university wants to make them,” Dean said. “But so far, the university hasn’t been making fair or reasonable proposals on the core issues.”

For Higbie, who bore witness to public divestment from academic workers in California since the late 60s, the UAW strike culminates both the UC’s unlawful practices and larger neoliberal failures in modern American society.

“The pandemic, the global financial crisis, student loan debt, the climate crisis — it feels as though there are multiple overlapping things hitting us all at once, and it’s beyond any individual’s ability to deal with,” Higbie said. “So I do think there is a change in attitude, especially among younger people, towards the idea of a labor movement.”

As final exams approach and graduate workers stick to their picket lines, Dean and Akhtar remain confident that the UC can no longer intimidate their way out of the labor movement they helped create.