“The 1975” are probably “the biggest band that nobody’s ever heard of,” at least according to frontman Matty Healy. The English band’s sound has been dubbed “unclassifiable” by Spin — veering from arena rock banger “Sex” to the trap-tinged “I Like America & America Likes Me.” Still, “The 1975” have never approached anything too hardcore. But on Aug. 22 they released the second single, “People,” from their upcoming album, “Notes on a Conditional Form." It was loud. It was fast. It was punk.

“People” clocks in at 2 minutes and 40 seconds. Heavy guitar and fast drums back Healy’s grim portrait of the modern world, laced with the occasional expletive. He sings, “You don’t have any money. We’re all just gonna try our f--king best.” Much of the song is Healy repeating the chorus over and over again: “People like people, they want alive people.” The video kicks up the intensity and even comes with a warning for those with epilepsy.

As well-known genre experimenters, “The 1975” aren’t necessarily shifting their sound from the pop rock spectrum to focus on punk. Fans will have to wait for the next album to know for sure. Still, “People” is a pivotal moment for the English quartet. When the band headlined Reading Festival this year, Healy kicked off the set with “People,” which had only been released the night before. He catapulted into the song and fans already knew the words. “The 1975” are arguably one of the biggest bands at the moment, as shown by their numerous festival appearances. Three of their albums hit number one in the U.K. and one in the U.S. If a musical act of this stature presents their embodiment of punk at the forefront of their image, could we be headed for another punk revolution?

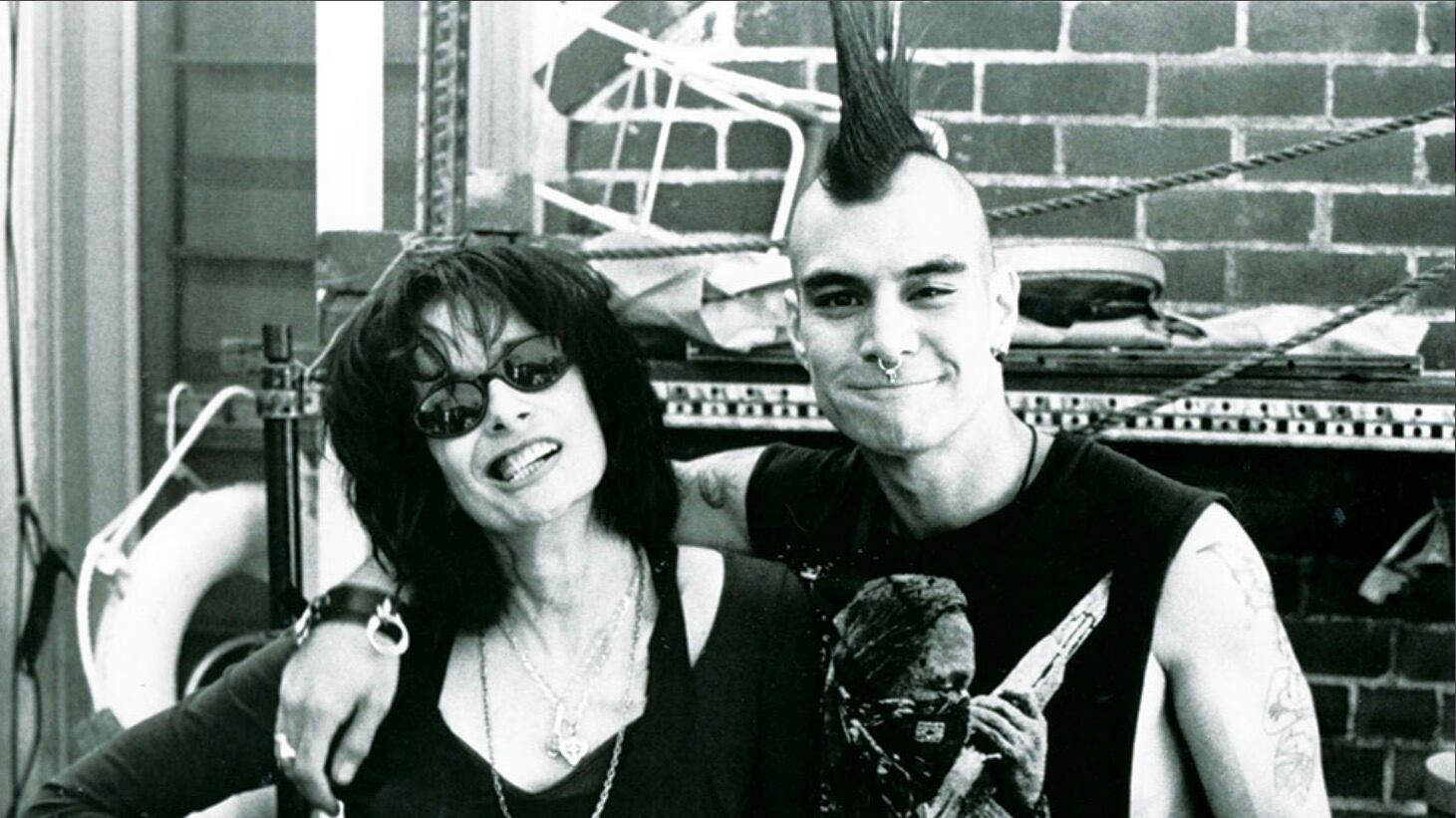

“The whole premise [of punk rock] was let’s just try to tear down tradition. Let’s change the world,” says Penelope Spheeris, director of “The Decline of Western Civilization” documentary, which captured the L.A. punk scene of the late 70s.

Can the authenticity of pure punk rock truly coexist with the digital world?

Changemakers have stepped up as the political climate has grown more intense. New York Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and the students who survived the Parkland shooting are taking actions that step outside the lines of conformity. And so is 16-year-old global climate change activist Greta Thunberg, who even earned a mocking from President Donald Trump. “The 1975” featured her on the opening track of their upcoming album in the form of a musically-backed spoken word essay about climate change. “Greta is the most punk person I’ve ever met in my life,” Healy told NME.

Spheeris said she first started noticing a major presence of punk rock in the mid-70s.

“It was the first time I personally had ever seen such a major social political and just a static shift that was guided and driven by music and by young people,” she says.

Alice Bag, vocalist of “The Bags,” a band from the first Los Angeles punk wave, says punk was music for outsiders who were trying to do something creative and out of the ordinary.

“If you were to go to a show at the time you would see people that look unlike any you've ever seen before,” she says. “It was a very inclusive scene where… women in stiletto heels [pogoed] next to somebody in tennis shoes next to somebody in maybe a designer type outfit that they had designed themselves.”

People think of punk as leather jackets and mosh pits dominated by male energy, according to Bag. But in the early days, it was about being inclusive.

Bag found her place in the punk scene. She grew up in East L.A. and came from an abusive household and needed an outlet. When she got to the stage, she had rage to work through.

“I was definitely being aggressive on stage,” she explained. “I wanted to shake people up and I wanted them to dance crazy, but it was about working out their feelings through music.”

Still, Bag acknowledges the male dominance that came to take over the scene, which was met by the female-led Riot Grrrl Movement. Bands like Sleater-Kinney, Bikini Kill and L7 came to rise. Bikini Kill frontwoman Kathleen Hanna would chant “girls to the front” for women and girls to come closer to the stage and to feel safe at shows.

This was in the ’90s and aimed to take back the punk space.

“You can't make us feel like we don't belong here,” Bag explains. “We want to see the shows and we're going to create a space for ourselves.”

Bad Cop / Bad Cop drummer Myra Gallarza first started going to shows in the early ’80s as a preteen.

“Back in the day it was hard to be a punk,” Gallarza said. “You had to be tough.”

Gallarza witnessed a lot of misogyny in the scene. When she and friends would go to shows, she says they would head into the mosh pit holding hands. In spite of that, Gallarza found her place in punk rock.

“Hearing fast loud aggressive music to me was like, yes this is me. This is what I love,” Gallarza said. “This is what defines me.”

As bands like Limp Bizkit and Korn became popular, a new sound emerged in the late ’90s and into the early 2000s. Different genres, like nu metal and rap rock, came into the mix, with bands like System of a Down and Papa Roach. Recently, Gallarza says the bands that dominated in the ’80s are making comebacks, like Black Flag and the Circle Jerks. Events like Punk Rock Bowling, a punk festival in Las Vegas, brings new and old bands together.

“We have bands that have been around for 25 years that are still doing it,” Gallarza said. “Punk has always been around and will always be around.”

What started as a youth movement, the punk scene can still be found in Los Angeles backyards. Sebastian Rodriguez started playing in bands when he was 13. By 2017, he decided he wanted to bring something different to the table. Now as the frontman of the Pantheons, Rodriguez and crew bring melodic goth rock to the scene.

“You could leave the scene for a few months or a year and come back to it and it’ll be completely different,” Rodriguez said. “Different waves of kids come around.”

The rotating crowd can be an amicable community, Rodriguez explains, but can also be cause for divide. Brawls sometimes break out. Gangs occasionally are involved. However, he sees a new dilemma among the younger crowd. Rodriguez categorizes two groups: one that is politically conscious and the other that uses punk as an outlet.

“Social media really changed how the scene is completely because now everybody has eyes on them,” he said. “Everybody does everything carefully.”

Still, Rodriguez emphasizes the overall sense of camaraderie. With age restrictions at venues, the backyard scene will always be a place for younger kids to find themselves.

“The thing that is lacking in mainstream music… they find in all this,” Rodriguez says. “The violence, the freedom, the aloofness, not caring. It’s perfect.”

Like Bag’s description, Rodriguez describes the wide variation in how people dress. You’ll see the classic street punks in leather jackets and girls who go for extravagant makeup looks like they’re from a Siouxsie and the Banshees video.

Generacion Suicida is a punk band that grew up in the L.A. scene. Since forming in the late aughts, Generacion Suicida has traveled the world and been hailed by Kerrang! magazine as L.A.’s “most authentic punk band.” Their sound is more melodic than the raw hardcore sound, which was the scene’s predominant sound when they first formed. Their first show was at the Piñata House in South Central, which used to be a meeting place for bands to sneak into May Day Protests and play in the streets during protests. The last time frontman Tony Abarca went to a show at the Piñata House around 2012, he says the cops came, tore down the fence and the SWAT team showed up.

“Back in the day, it was like, you played if you were lucky,” Abarca said. “Everybody wanted to play before we get raided [by the cops]. I think that gave us a certain style of playing really fast.”

In traveling to places like Spain and Japan, Abarca has seen punk manifest in all sorts of ways. Ultimately, he sees punk as inclusive.

“When I go to, for example, Europe and see the punks over there, they seem to be very active… changing the way society works,” Abarca says. “It’s really appealing for someone that doesn't have much. You’re an outcast and you’re among all these other people who also self-proclaimed outcasts. Suddenly you feel like you’re at home.”

“I honestly was kind of floating on a sea of confusion philosophically until I found punk rock and all of a sudden my identity kind of solidified,” Spheeris says.

Spheeris identifies as a punk to this day. It’s something so core to her identity she typically refuses to speak at panels about punk philosophy.

“When you start over-intellectualizing it, it evaporates,” Spheeris says. “Analytical studies on punk rock doesn’t make sense to me.”

She is sometimes disappointed in the younger generation when she sees them buy into what she refers to as the “Kardashian mentality,” the acquiring of material goods to feel rewarded. Nevertheless, Spheeris sees punk as an “absolute necessity.”

“The way the world is now sucks so bad that generations to come are in trouble,” she says. “We have to do whatever we can to improve the world and that’s part of that whole punk philosophy. To do what’s best for everybody... I couldn’t live without it.”